If This is a Man - The 1947 version

If This is a Man, Primo Levi’s first book, was first published by the Turin publisher De Silva in the fall of 1947. How the first version of this book was written, how it came to be published, and how readers received it were the result of circumstances that mapped out an uneven road full of surprises. Here, we can go down this road again with the aid of a wealth of images and rare texts.

1. The "first-born" book

If This is a Man is Primo Levi’s first book, which he wrote after he survived eleven months of prison in the Auschwitz concentration-extermination camp. In several conversations Levi defined his book as his “first-born.”1Mladen Machiedo, “Riječ će preživjeti. Razgovor s Primom Levijem” [The word will survive: Conversations with PL], Republika [Zagreb]», 1 Jan. 1969, pp. 47-48. The conversation took place in Turin 28 Oct. 1968 and was anthologized in Primo Levi, Opere complete, ed. Marco Belpoliti, vol. III, Conversazioni, interviste, dichiarazioni, (Torino: Einaudi, 2018), 32 (30-34). See Carlo Paladini, “A colloquio con Primo Levi” (Pesaro, 5 May 1986), Lavoro, alienazione, criminalità mentale. Ricerche sulle Marche tra Otto e Novecento, ed. Paolo Sorcinelli (Ancona: Il lavoro editorial), Nov. 1987 (Quaderni Iders, n. 6), 147-59; now in Levi, Opere complete III, 668 (667-81).

The book was published in the fall of 1947. This original version begins the story in the internment camp for Jews in Fossoli, near Carpi, in February 1944 and ends it with the liberation of Auschwitz by the Soviet army on January 27 1945. Auschwitz is in Upper Silesia in the Polish territory occupied by the Nazi army. Levi was imprisoned in Auschwitz III-Monowitz, one of the 44 satellite camps, named Buna, the German word for synthetic rubber. Buna, with its 10,000 prisoners, got its name for a synthetic rubber factory that was being built by the slave labor of the deportees, a factory that never started to produce anything.

Levi managed to survive in the concentration because an Italian worker, Lorenzo, secretly gave him extra food and because he was “hired” for the Buna laboratory and so could spend his last months of imprisonment safe from the cold and from hard labor. As someone with a degree in chemistry, he had to undergo a disconcerting oral examination that is one of the highlights of his story. In the mid-January 1945, he had the good fortune to be stricken with scarlet fever and confined to the camp infirmary. In this way, he was not called upon to evacuate the camp and march towards Germany. By this time, the Germans were hard pressed by the Red Army and led prisoners on a march that killed 80% of them.

2. A book "written right away"

“If This is a Man is a book that was written right away.”2Incontro con Primo Levi, Leo Club, Cuneo, Sept. 1975, in Levi, Opere III., 68 (64-77). Primo Levi said this in Cuneo in September 1975 to some of his readers he was meeting with, but this is something that needs to be interpreted. As is said, the original version of his first work appeared in fall 1947. This was almost three years after the liberation of Auschwitz. By that time, dozens of eye-witness accounts of Nazi concentration camps had appeared. However, most of these were about political prisoners. There were only seven reports by Jewish ex-deportees.3Anna Baldini, “La memoria italiana della Shoah (1944-2009),” in Atlante della letteratura italiana, eds. Sergio Luzzatto & Gabriele Pedullà, vol. III, Dal Romanticismo a oggi, ed. Domenico Scarpa (Torino: Einaudi, 2012), 758-63. Among these, If This is a Man was the last to be published before the years of prevailing silence set in about the extermination of the Jews– a silence that did not envelop Italy alone.

If we read the chapter “Die drei Leute vom Labor,” we can find out that Levi had already scribbled some short notes in the Buna laboratory, but that he had to destroy them because he would have been shot immediately if the Nazis had found them on him. Nevertheless, he kept on wanting to put something down on paper. He wanted two resources that were rare in the camp – solitude and thought. Rare as they were, they were the source of sharp pain:

The pain of remembering, the old ferocious suffering of feeling myself a man again, which attacks me like a dog the moment my conscience comes out of the gloom. Then I take up my pencil and notebook and write what I would never dare tell anyone.4Primo Levi, Se questo è un uomo, versione 1947, in Opere I, 108; If This is a Man (London: Penguin, 2002, 1979), p. 148.

Thus Levi had already tried to write in Auschwitz, but, as far as we know, he did not write in the months immediately after his liberation. His “truce,” a word that gave Levi’s second book a title, was an adventurous middle period. During his peregrinations that stretched out for over eight months, he travelled across Europe. His fellow travelers were combatants, veterans, or victims like himself. They were part of the same history and geography that the concentration camps are etched into. They were people to swap stories with along the trek. To do so was consoling, but these people were not the general public. As resonated solemnly at the end of the chapter, “Ka-Be,” the witnessing – i.e. “the evil tidings of what man’s presumption made of man in Auschwitz”5Opere I, 36; ITIM, p. 61 was something that had to be taken to all the others: those who were far away, those who were never there, those who did not know yet, those who preferred never to know, the indifferent, the resistant, the incredulous, the persecutors themselves and their direct and indirect supporters. This was the public that Levi sought out then and was always to seek out thereafter.

Levi’s abstention from writing before his return to Italy had a noteworthy exception. A Soviet government commission asked about 3,000 ex-deportees of various nationalities to document their experiences in the concentration camp in Oświęcim (the original Polish name of Auschwitz). This was an early investigation that outlined the key role Auschwitz played in the “final solution.” Although the investigation was still a bit rough, it was sufficiently authoritative. The investigation revealed the structure and functioning of the industry of death and the number of victims. Two Italian Jews were among those who compiled evidence – Leonardo De Benedetti, a 47-year-old doctor. and Primo Levi, a 25-year-old chemist. Their Rapporto sulla organizzazione igienico-sanitaria del Campo di concentramento per Ebrei di Monowitz (Auschwitz - Alta Slesia) / Auschwitz Report was in all probability the first testimony of a scientific nature on the extermination camp in all of Europe.

It is very likely that the Report had had a first draft – shorter and perhaps written in French – which one day might be rediscovered in some archive of the ex-Soviet Union. Instead, the text that we know today was a version conceived for the Italian readers who knew hardly anything about the concentration camps. Levi and De Benedetti had it published in the prestigious Turin-based journal, Minerva Medica, on November 24 1946. After decades of oblivion,6 Alberto Cavaglion, “Leonardo ed io, in un silenzio gremito di memoria”: Sopra una fonte dimenticata di Se questo è un uomo,” conference paper at Convegno Primo Levi: memoria e invenzione, San Salvatore Monferrato, 26-27-28 Sept. 1991; now in acts of conference (same title), ed Giovanna Ioli, (San Salvatore Monferrato: Edizioni della Biennale Piemonte e Letteratura 1995), pp. 64-68. Alberto Cavaglion retrieved the text, which was then published in a philological edition7Matteo Fadini, Su un avantesto di Se questo è un uomo (con una nuova edizione del Rapporto sul Lager di Monowitz del 1946), Filologia Italiana 5 2008 [but 2009], 222‑35. and a newer annotated edition8 Primo Levi (with Leonardo De Benedetti), Così fu Auschwitz. Testimonianze 1945-1986, eds. Fabio Levi & Domenico Scarpa (Torino: 2015, Einaudi), pp. 3-30 (text), 145-58 & 205-8 (comments and notes); Auschwitz Report (London: Verso, 2006). before it was included in the Italian complete works, Opere complete.9Levi, Opere I, 1177-94.

The report is a militant text commissioned and written while the war was still going on and/or immediately afterwards. It is a text to read and study in itself and not as a first draft of If This is a Man. The report was amazing in its ability to collect, recollect and organize complex and detailed information. It is as anthropological as is it clinical, as political as it is scientific. The authors De Benedetti and Levi were two grassroots-level authors writing from the on ground-level. They amaze us in their ability to overcome the lack of knowledge about time and space, which was inflicted upon them in the concentration camp before any other humiliation was.

Thus the Report was really “written right away” but this is something that is also true about If This is a Man. In a 1974 television interview, Levi answered a question about the birth of his first book “as a structure” in this way:

It was not born. It came out of a series of stories. It was born inside out and maybe it looks that way. I wrote the last chapter first because it was the most urgent and the freshest in my memory, but I didn’t mean to write a book. I thought I would put down some notes to tell stories to a greater number of people, but I didn’t have a plan to write a book. The plan came up bit by bit when I noticed that these episodes made up a story that I could arrange chronologically, that they were, all in all, a chronology.10Il mestiere di raccontare, trasmissione Rai ed. Anna Amendola & Giovanni Belardelli, 20 May 1974; this is the first of three episodes dedicated to Levi. We thank the Archivio Nazionale Cinematografico della Resistenza, Torino.

3. Places, dates, genres

It was only in the second and definitive 1958 version of If This is a Man that the book closed with an indication of when and where it was written: “Avigliana-Turin, December 1945 - January 1947.” Avigliana was the town where the Montecatini-Duco factory was located, where Levi was hired as a chemist on January 21 1946. This was his first steady job after he returned to Italy. From that moment on, his work and his writing overlapped. He put it this way in “Chrome,” the twelfth story in The Periodic Table:

I had benignly been granted a lame-legged desk in the lab, in a corner full of crashing noise, drafts, and people coming and going carrying rags and large cans, and I had not been assigned a specific task. I, unoccupied as a chemist and in a state of utter alienation (but then it wasn’t called that), was writing in a haphazard fashion page after page of memories which were poisoning me, and my colleagues watched me stealthily as a harmless nut. The book grew under my hands, almost spontaneously, without plan or system, as intricate and crowded as an anthill.11Primo Levi, The Periodic Table (New York: Penguin, 2000;1975), p.127.

Therefore there were weeks and weeks of being notes scattered around by Levi’s urge to try to recall. This was before a structure began to map itself out. The date “December 1945” referred to the first phase of this feverish pursuit of facts.

The typescripts of the first draft of the final chapter, “The Story of Ten Days,” were dated February 1946. The earliest chapter that Levi managed to put in order was that the chapter with the simplest structure – a diary. In Levi’s definitive version, If This is a Man perfectly fuses the chronological line of events with the thematic progression of the discovery of the concentration camp by the witness-narrator. This hold true for both editions of the work – the 1947 and the 1958 ones. Every new topic that Levi takes on in his single chapters – the journey, the entrance into Auschwitz, the infirmary, sleep and dreams, forced labor, and the selections for the gas chamber – corresponds to a calculated step ahead in the calendar along a span of months and seasons. Diary and story blend together smoothly. The same is true for the description of events and the reflections on the events themselves.

Today we know the dates when several chapters of the book were written (or at least, their first drafts) thanks to a typescript that Levi sent to his cousin Anna Foa (married name, Yona), who was living in Massachusetts, in the hope that she could help him find a publisher in the United States. In fact, this was even before the work appeared in Italian. The chapters and dates are the following: “The Canto of Ulysses,” February 14 1946; “Kraus,” February 25; “Chemical Examination,” March; “October 1944,” April 5-8; “Ka-Be,” June 15-20.12 Marco Belpoliti, Note ai testi, in Levi, Opere I, 1455-56.

When Levi wrote the famous chapter, “The Canto of Ulysses,” Levi did not yet know that his friend Jean Samuel – nicknamed “Pikolo” in the concentration camp – had survived the evacuation march that involved all the healthy prisoners on night between January17 and 18 1945. Jean was traced by another fellow-deportee, Charles Conreau, who had managed to return home before Levi and who had sent him a letter from France. When Levi returned to Turin (October 19 1945), Levi found Charles’s letter waiting for him. He answered immediately, asking him, among other things, to look for Jean Samuel in Strasbourg. Charles managed to find Jean at the beginning of March 1946 and gave Jean Levi’s address in Turin. Jean wrote Levi on March 13 and Primo answered him March 23 in a long letter. Among the many things that he wrote, this is of particular interest: “J’écris: des poésies, des essais, même des contes rapport à la vie du Lager13Jean Samuel avec Jean-Marc Dreyfus, Il m’appelait Pikolo. Un compagnon de Primo Levi raconte. (Paris: Laffont, 2007), p. 87. ” [I am writing: poems, essays, even stories related to the life of the Lager]. Again in “Chrome,” Levi wrote in his first months after his return “I was writing concise and bloody poems.”14 Levi, The Periodic Table, p. 126. In this letter, which was written while he was drafting his “first-born” book, Levi already distinguished between “essays” and “stories” and wrote that it was particularly audacious to write “stories” about Auschwitz. All this meant that he classified the texts he was gradually working out as ones prevailingly narration or non-fiction. Certainly, the most essay-like texts were “This Side of Good and Evil” and “The Drowned and the Saved.”

In that first letter of March 23 Primo confided to Jean that he wrote about him in one of his stories: “Tu trouveras ça bizarre” [You’ll find this bizarre]. Later, on May 24, Levi sent him a non-definitive draft of “The Canto of Ulysses” in Italian.15Samuel-Dreyfus, Il m’appelait Pikolo, pp. 95-97. However, we should look at an earlier letter from April 6 1946,16 Ivi, p. 87. where Levi gave a strange and extraordinary definition to the texts he was producing for If This is a Man. They were, in French, machins. “In other words, gadgets…. Levi certainly wrote this out of modesty. However he might have said this for another reason. Maybe he clearly intuited that his various ways of describing the experiences of the concentration camp – ways that were experienced at the same time and in the same environment – were ways that could not be classified through traditional literary genres. All together, they had the amphibian and ineffable quality of works that produce a genre in themselves.”17Sergio Luzzatto, “Lettere a Pikolo” (Corriere della Sera, 18 Jan. 2008), in Id., I popoli felici non hanno storia (Roma Manifestolibri, 2009), pp. 253-55.

4. Publishers’ refusals and leads

If This is a Man was ready at the beginning of 1947. Without giving many details, Levi said that he presented the book to two or perhaps three publishers, where he was rejected. The only publisher which we have any concrete news about is Einaudi in Turin. Two editors who were also writers read the manuscript – Cesare Pavese and Natalia Ginzburg. Ginzburg, whose maiden name was Levi but was not a relative of Primo, was of Jewish origin. Three years earlier, she had lost her husband, Leone Ginzburg, who had founded the publishing house along with Giulio Einaudi in 1933. Leone Ginzburg was a celebrated expert on Slavic studies, history writer, and anti-Fascist conspirator. He was one of the greatest heads of Giustizia e Libertà [justice and liberty], the movement that Levi took part in during his brief partisan experience. Ginzburg died February 5 1944 in a Roman prison after being tortured by his Nazi jailers.

Einaudi was a publishing house that theoretically should have found itself in tune with Levi. It had the potential to grasp the esthetic value of the work. Its rejection of Levi was scandalous, but not only in Italy. After Levi’s death, Ginzburg admitted that she had made a stupid mistake 40 years earlier. Nevertheless, from the perspective of 1947, the war had already been over for two years and the books of memoirs that evoked the horrors of the war seemingly had saturated the market, even though they rarely brought up the subject of the deportation of the Jews. Einaudi especially aimed at publishing books that looked ahead to the future of a country that had to be rebuilt. At first glance, Levi’s book did not seem to fit in. Even Levi’s style diverged from the literary climate of that time. The so-called neorealist writers modelled themselves on Americans, Hemingway above all.

The prejudice against concentration-camp memoirs did not work against Levi alone, an unknown with no influential friendships. In 1947 Einaudi also rejected Robert Antelme’s L’Espèce humaine [On the Human Race], which told of his experiences as a political prisoner at Buchenwald and Bad Gandersheim. His book was rejected even though he had been a director of the resistance and the French Communist party, even though he was married to Marguerite Duras, and even though Elio Vittorini had advised that the book be published. At the time Vittorini was the most authoritative consultant at Einaudi.18 See Marco Belpoliti, “Levi: il falso scandalo,” La Rivista dei Libri X, 1, Jan. 2000, pp. 25-27; Domenico Scarpa, “Storie di libri necessari. Antelme, Duras, Vittorini,” in Id., Storie avventurose di libri necessary (Roma:Gaffi, 2010), pp. 165-202; 425-34; cf. Robert Antelme, On the Human Race (Marlboro: Marlboro Press, 2003). Only many years later did Einaudi get about to publishking both works, Antelme’s in 1954 and Levi’s in 1958.

On March 29 1947, the newspaper presented the first episodes, explaining that the selections were taken from “a book to be published soon, ON THE BOTTOM, regarding the Auschwitz elimination camp.” Thus the book was complete but had not found a definitive title yet. As we will see, this uncertainty was to last up until the last moment. In the meantime, Levi’s life took its course. He resigned from Duco and ventured into setting up a private chemical laboratory with his friend Alberto Salmon. It was a commercial failure, which he wrote about in two episodes of The Periodic Table, “Arsenic” and “Tin.” In September, Levi married. At the end of that summer the Florentine journal, Il Ponte [the bridge] published “October 1944,” the chapter on the selections for the gas chamber, in its monographic issue Sulla Germania [on Germany], dated August-September.

5. Franco Antonicelli and De Silva Publishers

However, it is at this point that the book finally found a publisher. Primo’s sister, Anna Maria, who took part in the resistance as a partisan messenger, found a way to have the typescript published. She gave it to Alessandro Galante Garrone to be read. He was a historian and magistrate who had served as the representative of the Partito d’Azione on the Piedmont Comitato di liberazione nazionale [national liberation committee]. On March 28 1947 Garrone wrote Franco Antonicelli, who presided over the Piedmont CLN as representative of the Partito liberale, and who then directed the publishing house, Francesco De Silva:

Dear Franco, I am leaving you the manuscript of Primo Levi that I told you about. I don’t think I am being fooled in judging it superior to what we have happened to read so far in this genre. However, I prefer to trust your more secure judgement. I think that it is an outstanding historical and human document because he presents us with an inexorable portrait of that atrocious world and involves us in moral issues. Not only, it is, page after page, a beautiful thing. To get a quick idea of the work, see, especially, the chapters: “October 1944,” “Chemical Examination,” “Kraus,” and especially the terrible “Story of Ten Days.19The entire text of this letter first appeared in the appendix of Massimo Bucciantini, Esperimento Auschwitz (2011), which is now in the anthology Lezioni Primo Levi, eds. Fabio Levi & Domenico Scarpa (Milano: Mondadori, 2019), pp. 89-90.

Like Primo Levi, Franco Antonicelli (1902-1974) studied at the D’Azeglio Liceo Classico, the classics-based secondary school where he had also taught. He had reached some fame in the early 1930s when he created a Biblioteca Europea, a “European library” for the Turin publishing house, Frassinelli. Its first title was Babel’s The Red Cavalry. A little later Frassinelli published Melville’s Moby-Dick, translated by Cesare Pavese (1932), and Kafka’s The Trial, translated by Alberto Spaini (1933). These were authors that were both novelties for Italy. Antonicelli founded the De Silva publishing house in Turin in 1942, but it started functioning completely only after the war.

Even after Einaudi’s rejection, the publication of If This is a Man matured in anti-Fascist circles in Turin. And it is Antonicelli that we can thank for the title that we know now. Perhaps Levi had at first thought of the title, Stories of Men without Names.20 See Album Primo Levi, eds. Roberta Mori & Domenico Scarpa (Torino: Einaudi, 2017), pp. 70-71. Then he chose On the Bottom and later, The Drowned and the Saved. This was the title with which the manuscript reached De Silva publishers. However, Antonicelli had the flash intuition to eliminate the imperative, “Consider,” from one of the verses of the poem-epigraph, coining the definitive title, If This is a Man.

De Silva publishers finished printing Levi’s “first-born” book on October 11 1947. It was a 198-page volume that came out in the series, Biblioteca Leone Ginzburg, which was subtitled as “Documents and Studies in Contemporary History.” Ginzburg had been a friend and brother to Antonicelli from the very end of the 1920s.

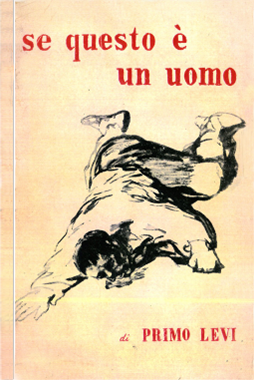

It is very probable that Antonicelli was the person who chose Goya for the book jacket. Goya’s design was executed with wash, brush, on bister (dark-yellow) laid paper. This design is Number 49 in his so-called Álbum C, which is conserved almost entirely in the Museo del Prado, Madrid. The album collects designs from 1808-14: night visions and images of people condemned by the Inquisition. Goya entitled Number 49 La misma [The Same] and is similar to the figures in the series Disasters of War, and to the canvas dedicated to the execution by firing squad on May 3 1808. Goya’s design was retouched graphically before it was placed as an illustration of Levi’s book.

A publisher as elegant as he was concrete, Antonicelli did everything he could to promote If This is a Man on the bookstore market and among literary critics. He printed a pamphlet where he presented it as “a new writer’s book,” insisting on its specifically literary value: “There is no book in the world about the same tragic experiences that has the artistic value of this book.” The fourth and last page of the pamphlet reproduced Levi’s handwritten poem-epigraph. The verse “Consider if this is a man,” is colored in red.

Levi also committed himself personally. In the October 1947 issue of the monthly, L’Italia che scrive [Italy that writes], he wrote the column Presento il mio libro [I present my book], which was entitled “If This is a World”:

If not in deed, then in intention and in conception, my book was already born during the days in the concentration camp. The need to tell “the others,” to make “the others” take part, was something that took on the features of an immediate and violent impulse before the liberation and after, so much so that this impulse rivaled our other basic needs. The book was written to satisfy this need, thus to free my inner self first of all.

This is where its fragmentary nature comes from. The chapters were not written in logical succession but in the order of urgency. The work of joining and blending together was done according to plan and was done afterwards.

I have avoided crude details as well as temptations to be polemical and rhetorical. Those who read them could have the impression that the other, much more atrocious accounts of imprisonment have gone beyond the limits. This is not so. All the things that were read about were true, but this was not the face of truth that I was interested in. Neither was I interested at all in telling the stories of the exceptions, the heroes, and the traitors. Rather, because of the way I was and the way chose to be, I tried to keep my attention on the many, on the norm, on the ordinary man, not vile and not saintly, on somebody who was great only in his suffering but was unable to understand it or to contain it. It seems to me superfluous to add that none of the facts were invented.

I am not at a level where I can judge my book: it could be mediocre, bad, or good. In any case, I hope it is read, not only out of my ambition but also in the faint hope that I managed to make the readers notice that these things had to do with them.

This book was not written to accuse and neither was it written to provoke horror or execrate. The teaching that flows from it is one of peace: people who hate break a law of logic before they break a principle of morals.

6. Critical reception

De Silva printed 2,500 copes of If This is a Man, a good number for a non-narrative debut. A few more than 1,500 copies were sold. There were a few reviews but not very few – more than twenty, a good result for a little publisher and for a work dedicated to a topic that was no longer topical.

Levi’s book was reviewed mainly in newspapers and magazines in Northern Italy, mostly those of the left – communists, socialists, social-democrats and ex-members of the by-then dissolved Partito d’Azione. Nevertheless, there were also reviews in the Corriere d’informazione, which was the afternoon edition of the most important national newspaper, the Corriere della Sera from Milan. In Switzerland, there were articles in the Gazette de Lausanne and the Weltwoche from Zurich.

The timeliest opinion was that in the most important newspaper in Turin. On November 26 1947 Arrigo Cajumi reviewed If This is a Man together with another debut work, Italo Calvino’s The Path to the Spiders’ Nests. Cajumi’s review appeared on the first page of La Stampa under the headline, Immagini indimenticabili [unforgettable images].

His review praised If This is a Man as a work that “spontaneously hinges on a capital problem: that of man who lives at the will of another man in the modern world.” Besides Levi, the reviewer recommends Calvino: “As much as the first is measured and austere, the second is youthfully loose-tongued and fanciful.”

It was Calvino who wrote the most far-sighted review of If This is a Man, although it was published months later than the release of the book. In fact, the article came out on May 6 1948 in the Piedmont edition of the Communist Party newspaper L’Unità. Calvino called it “a magnificent book that is not only a very effective piece of testimony but also has some pages of authentic narrative power that will stay in our memory as some of the most beautiful – belle – pages in the literatures of the Second World War.” When Calvino used the adjective “beautiful” – belle – to define the style of Levi’s book in addition to its content, he was one the first people to suggest that Levi was a writer in addition to a witness. One year later he seconded his judgment when he wrote again about concentration-camp diaries and mentioned Levi again in his essay “La letteratura italiana della Resistenza” [Italian literature of the resistance]:

I will limit myself to naming what – and I believe I am not wrong – is the most beautiful of all – Primo Levi’s If This is a Man. It is a book that is really insuperable in its sobriety in language, power in images and, sharpness in psychology.21Italo Calvino, “La letteratura italiana sulla Resistenza,” Il movimento di liberazione in Italia I, 1 (July1949), now in Id., Saggi 1945-1985, ed. Mario Barenghi (Milano: Mondadori, 1995), p. 1499 (1492-500).

7. Two long-distance dialogues, two literary prizes

De Silva published a small-format accordion-shaped catalogue for April-May 1948 that dedicated one of its pages to If This is a Man. The catalogue reported, “The wife of the famous scientist Enrico Fermi will translate this exceptional chronicle of the inferno of Aushwitz [sic] for Americans.” Laura Capon, Fermi’s wife, was born in Rome in 1907 of Jewish descent. Her translation remained incomplete. However, her papers, conserved at the Special Collections Research Center of the University of Chicago Library, contain a 9-page synopsis of the book for the benefit of eventual publishers and translations of the chapters, “A Chemistry Examination” and “History of Ten Days.”

In the summer of 1948 If This is a Man competed for two literary prizes – the Viareggio prize, and the Saint-Vincent prize for prose. At Viareggio, the book made just the final 21 books of the first selection. At Saint-Vincent, where Natalia Ginzburg was on the jury, the book reached the final phase along with the winner Angelo Del Boca, Luigi Bartolini and Alberto Moravia.

Despite these partial successes, Levi described himself as he was in 1948 – it is worthwhile to note this, looking back: “I the discouraged author of a book which seemed good to me but which nobody read.”22 Levi, The Periodic Table, p. 153. This appeared in the last paragraph of “Nitrogen” in The Periodic Table. However, near the end of that year a letter dated November 3 arrived from Trieste:

Dear Mr. Primo Levi, I don’t know if you would be pleased to hear me say that your book If This is a Man is more than a beautiful book. It is a fatal book. Really, somebody had to write it. Fate wanted it to be you. It is fatal as was Silvio Pellico’s Le mie prigioni [My imprisonments] last century. Was it successful? Was it not successful? I know nothing about it. The horror and, more than that, the disgust about what is happening are cutting me off more and more from everything that is being written and said today. And I got hold of your book, too, by chance. There was little chance for me to buy it. But, as soon as I began to read it, I couldn’t put it down. Now it’s like I had gone through the experience of Auschwitz personally. If I had anything to do with it, I would make it a school textbook. But the people responsible (if people can be responsible for anything) for the concentration camps would do anything to prevent this. Unfortunately, the immense crisis of nastiness and stupidity that began in 1914 needs some centuries to exhaust itself. I have the impression that your book can live on even beyond the times of crisis. Because many others have described those horrors, but they all have done this from the outside. Nobody – at least as far as I know – has felt them again and rendered them from the inside.

Umberto Saba closed the letter with the words “with gratitude and affection” and signed with his last name only. Before, he had asked Giulio Einaudi for Levi’s address, regretting that Einaudi had not published the book. Son of a Jewish father, Saba defined If This is a Man with an adjective that was important. In his personal lexicon, “fatal” was used to indicate that a work was written out of inescapable need. According to Saba, his verse Canzoniere [Songbook] published in 1945 was fatal. However, Scorciatoie e raccontini [Shortcuts and little stories], his short prose book published by Mondadori in 1946, was also fatal. At the beginning of this book, he asserts that those little nuggets of wisdom are “veterans, in some way, of Maidaneck. Majdanek (its exact spelling) was the second concentration camp after Auschwitz to be transformed into an extermination camp. The Red Army liberated the camp July 22 1944. News of this camp was some of the first news about camps to reach Italy. Saba sent Levi a copy of Scorciatoie as a present. Still today, no one knows how Saba had had gotten the chance to read If This is a Man.

8. Provisional epilogue

In 1949 De Silva had financial problems and ceded its activities and its warehouse of books to a publisher from Florence, La Nuova Italia. Several hundred unsold copies of If This is a Man remained. Levi used a remarkable word to indicate the natural disaster that destroyed them on November 4 1966 – “drowned.” They were drowned like the “the drowned” of the concentration camp and Dante’s Ulysses: “they were drowned in Florence during the flood because La Nuova Italia, which had obtained the rights of the books, stored the books in a cellar.”23 Giulio Goria, “Sono diventato ebreo quasi per forza: Conversazione con Primo Levi,” Paese Sera, 3 May 1982), in Opere III, 255 (252-55). By 1966 the new definitive version of If This is a Man had been in circulation for eight years.